In 2019, to commemorate the Gate’s 40th anniversary, Artistic Director Ellen McDougall sat down with journalist Susannah Clapp to talk about her memories of reviewing productions at the Gate Theatre, and its unique and inspiring role as a small, international, shape-shifting space.

Susannah Clapp is a theatre critic for the Observer and author of ‘A Card from Angela Carter’ and ‘With Chatwin’.

This is a transcript of their conversation which has not been edited.

EM

I wanted to start by asking you, when you think of the Gate, what are the shows that come to the forefront of your mind?

SC

Well, one of the very first shows that came to mind was Sarah Kane’s Woyzeck (1997). And I was absolutely riveted by it. Then, when I looked again on my list, I had forgotten – they hadn’t actually merged in my mind – but in the course of the last 20 years I’d seen two productions of Woyzeck at the Gate.

![1997 - woyzeck [jonathan bruun] ad david farr dir sarah kane photography by pau ros](https://www.gatetheatre.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/1997-WOYZECK-Jonathan-Bruun-AD-David-Farr-dir-Sarah-Kane-Photography-by-Pau-Ros-480x330.jpg)

A play that is not very often performed because it’s famously fragmentary and difficult and elusive. But that was very much one of the first ones [that came to mind] because of its intensity – an intensity which is of course enhanced by being so close to the action [in the Gate space]. But also because functionally I think in both of those productions they were very, it seemed to me, ‘total’.

I remember two things – one was the design opened up like a child’s toy and also the sound design reverberated around and underneath the stage, so that it was very complete. It was very fierce and as naturalistic as you can get with something which isn’t entirely joined up.

‘There are some things you can only do in a small space and there are some things that only the Gate does in a small space.”

Whereas Daniel Kramer’s production (2004) was entirely expressionist, with lots of people dangling from window frames and cages, and again there was an extraordinary noise under the stage, that sort of dying engine, a terrible gasp I remember. It also had a very good central performance by Edward

Hogg, very anguished. But it struck me as interesting that this little performed play had two different productions [at the Gate] and they were two of the first that came to mind to me. They do seem to me to combine and to suggest some of the strengths of the Gate: it’s both far-flung and ambitious but actually very tight and intimate. There are some things you can only do in a small space and there are some things it seems to me that only the Gate does in a small space.

I remember I noticed how extraordinary it was that this giant internationalism had landed in this small space.

The intimacy that you get [at the Gate] is something different. It’s not kitchen sink, and it’s not exactly to do with pleated, meticulous details of furnishing. That’s not perjorative of furnishing; I like furnishing, but there are things [the Gate] does that people elsewhere wouldn’t be able to do.

One of the things I’m thinking of is your [Ellen McDougall’s] production of The Unknown Island (2017) . When you had those amazing balloon animals and watering cans for a shower of rain. It’s an obvious point but it looked disconcerting, mysterious and funny. It would have looked ridiculous on a bigger stage.

I do tend to talk a lot about size because I’m so interested in the way that [Gate] stage can be re-configured to make an audience feel caught up in the action.

And The Unknown Island had the marvellous Rosie Elnile design. She is for me one of the great discoveries the Gate made.

I think I’m right in saying I saw her work first there and I loved that because it was a complete wrap-around design in which the whole audience was in a bubble with these sudden splashes of scarlet galleon. It was really extraordinary because it was very bold, but it was actually very small and you did feel really enclosed.

But there’s a paradox there because one of things I’ve been thinking about is your [Ellen’s] reign and how you made a feature of, certainly in your opening three productions, ‘breaking the fourth wall.’

‘You feel a pulse of differentness when you go to the Gate.’

I don’t like using that sort of language but of actors stepping outside the action, talking directly to the audience, sometimes involving the audience in the action, but always with a point. It always seems to speak to something that is actually within the drama of the play itself: it wasn’t simply a cheap, disconcerting trick. And obviously, again that comes back to the size of the theatre, because it’s both more disconcerting because people are so near than it would be in a bigger theatre, but it’s also more natural. There is a funny balance between natural and unnatural and I like very much the way, I think you in particular have done the flinging open occasionally of the window at the back of the auditorium so the outside kind of winks at you.

That’s always lovely in the theatre to be reminded that you are basically taking the theatre out and letting the outside world come in at the end.

‘Giant internationalism landed in this small space. It was extraordinary.’

EM

Yes. That’s something that I’ve always felt about that space. It’s funny and silly to me pretending that we can’t see the audience in a space like that. On that scale, with 75 seats, you can look everyone else in the eye. It feels intimate – it’s very interesting you say that it feels natural to the audience as well.

SC

It’s natural and surprising. The other thing – okay, I’m just talking about your work at the moment – that struck me, which I liked very much, and I had a great interest in the subject matter anyway but never expected to see it on stage, was Dear Elizabeth (2019).

What I liked about it is, it’s always very exciting to know something is going to be remade, particularly when it’s Jade Anouka and Jonjo O’Neill [performing]. I mean I was so lucky. But actually I think everybody [in the audience] was lucky in the partnerships they saw. But you wouldn’t have had, without a great degree of self-consciousness, an impromptu unrehearsed reading in a bigger theatre. And yet what I liked about it was that it was properly produced. The only problem I had was the swishing curtain at the back which was a bit like a [crematorium.]

EM

But actually for me, that was the idea. Because of the fact that they [the two characters – Robert Lowell and Elizabeth Bishop] are both dead. And there was an idea in the piece about presenting their total lives.

SC

That’s interesting. You see I’ve learned something! Never think you know better! What I also liked was the freshness and spontaneity of the verbal delivery, and it was very highly directed as well, I mean just in visual terms such as the pop-up dollar sign when Elizabeth wins the Pulitzer Prize and the pet toucan and so on. You didn’t feel you were simply being given something that could have been a much more instructional and reverential rendering of letters. It was really rich.

You didn’t feel you were simply being given something that could have been a much more instructional and reverential rendering of letters. It was really rich.

***

I started to be a critic in 1997 so, soon before Erica Whyman took over…

EM

Was it Mick Gordon? Or was it David Farr actually?

SC

Yes, it was when David Farr was Artistic Director.

‘When journalists… talk about the ‘average theatre goer’ they very often complain about the age of theatre-goers and how embarrassing it is to be in the theatre and how stuffy it is and so on. I would tell them to go to the Gate’

EM

[It was] his penultimate year (1996-1998).

SC

That makes sense. When I was looking [at my Gate archive], I wasn’t trying to look for representatives from each decade, but there were some from every decade that leapt out.

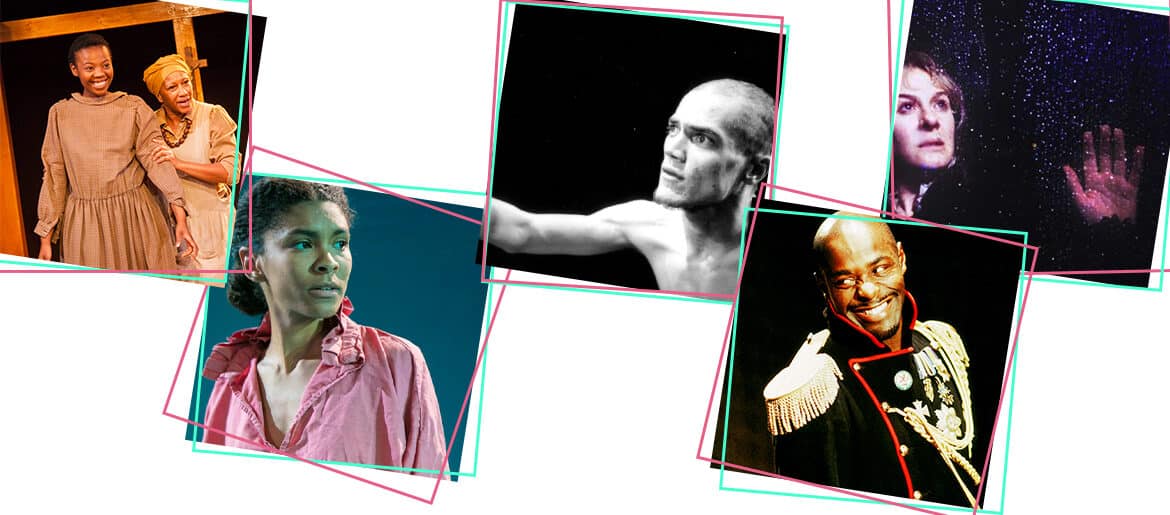

For example, I think in Thea Sharrock’s time, Emperor Jones (1983) was extraordinary, because it was such a daring thing to do, with Paterson Joseph. He was terrific.

The design – I’m afraid I can’t remember who it was, was it Richard Hudson? (It was Richard Hudson) It was a very good combination of visuals, lighting and sound design from Adam Silver and Gregory Clarke. The central image of a pit with bamboo stakes around it, around which the audience seemed to be gathered, as if we were

potentially, taunting this person – now it can’t have been like that all the time but that’s my memory. Obviously memory is very selective.

I remember this pit set, him pacing around and him disintegrating magnificently and yet somehow having managed to summon up this audacity and regal command beforehand. And when she [Thea Sharrock] left – it was a very witty thing to do – it hadn’t occurred to me how witty it was until I was thinking about it today, her last production was Ionesco’s The Chairs (2006). It was a brilliant thing to end with because, you know, it ends with people saying goodbye and I don’t think I realised at the time what a clever piece of programming it was. I think Ionesco is really difficult for English directors to do convincingly but she did pull it off. And then, in 2007, I think it was Ghosts.

EM

With Niamh Cusack?

SC

Yes. It was terrific. l think I liked it more than most of my colleagues. I remember it opened, or very near the beginning anyway, with panes of glass and streaming rain and her [Niamh Cusack] appearing behind it, as if she was the ghost.

And of course she’s in some way the person who’s haunted, not doing the haunting, which was a very brilliant device. Actually throughout I was very impressed. The script – Amelia Bullmore’s script – was very paired down, everything about the production was paired down. It didn’t have any element of flamboyant chicness about it and one might say there was something very Scandinavian in the elimination of unnecessary decoration. This plain wooden glass, plain speech, and very taut performances – not just Cusack. They were wonderful actors, particularly in that piece, they both felt very contained and also really gesturally vivacious, her [Cusack] in particularly, seemed to always be about to be moving, her hands were always trapped behind her; and that impressed me a lot.

Then, going later, I think this was a farewell production as well, The Convert (2017).

It was such an impressive piece of programming.

I tend to think that when people talk about international theatre in London since I’ve been a critic they haven’t often meant theatre from, or which has involved people of African descent.

‘Scale doesn’t mean restriction.’

What was so interesting about The Convert [was that] it had a really corrugated historical look at imperialism without actually ever seeming to be preaching. It also had a wonderful central performance from Mimi Ndweni.

She was terrific and it’s a part that’s quite easy to get wrong. She was extraordinary. You thought her smile was about to burst out of her face – it was too big to contain it. It was a very ambitious thing to see. And again there was a wonderful Rosie Elnile’s design which absolutely balanced the two of the themes in the play; the attempt at conservative decorum (which really meant being very white) yet always at the back were people in a heap of rubble. Perhaps the rubble came later but there was a moment where both seemed to be fighting on stage and to do that in so tiny a space!

Actually I think the floor actually cracked open at some point, it was amazing.

EM

One of the things that strikes me about that show was, in a really simple way, there were quite a lot of people in it, compared to a lot of the things that more recently we can afford to do. There is something the Gate space invites, and you’ve spoken to this already, about large scale productions in a small space.

SC

Yes. You never feel as if the theatre is ‘local’ – although I wouldn’t mind seeing, I don’t know what the requirements are, something local, that would be interesting as well, something that spoke to the local area. In question of scale though, that was interesting with Daniel Kramer’s production of Hair (2005). I mean I feel a little ambivalent about it because it’s not actually a show I particularly like, but you sure as hell felt like it was a bold thing to put on in that space. Having that nakedness so near you, the general tremendous ebullience of it bursting out of the stage was terrific.

Whether the ‘nearness’ in some sense is helpful. On the other hand I’ve seen some very big performances here. Paterson Joseph is one and the other which I remember at the time was very detailed and quiet but a big performance nonetheless was

Thalissa Teixeira in The Unknown Island – you could follow every movement of that play from just looking at her face. She was like a beacon – it was quite extraordinary, she wasn’t holding back.

EM

The other thing that interests me and again you’ve touched on it – formal experimentation is often a feature of the work.

SC

Do you think that’s to do with it being so very welcoming of international ideas? Maybe the two things are linked? At its most basic level I was very interested when Carrie Cracknell and Natalie Abrahami did a lot of work that used dance to lift the action, and that was lovely to see. You didn’t [see that] very often. Especially, it would be interesting to see how many things were seen at the Gate that have now become more common currency – not necessarily learning from it but have drifted into the national vocabulary. Especially when you’re dealing with something like Woyzeck, you are bound to be experimental. I know Michael Billington sees it as an essentially realistic play and I think he’s right in a way, that its impulses are naturalistic, were rooted in social drive, and social degradation. Nevertheless, its expression is of mental fracture, and therefore formally [it has] very disparate and peculiar development.

The extent to which you’ve used, I mean you in particular although it’s also true of others before, monologues. By the way, one, no two of the best things I’ve seen all year by women, in big theatres, have been monologues. When we are looking back on this period in theatrical history we can see how they barely existed 5 years ago – and suddenly here they are all the time.

People are no longer allowed, well, they were never allowed to say in my book, ‘I’m not quite sure whether this is theatre – it’s a monologue’. I don’t care about that sort of thing. And because of that I haven’t quite got to grips with your question about form because in a way it’s not something I think about separately from the piece – I think form breaks into the piece.

You feel a pulse of differentness when you go to the Gate without necessarily always thinking of it belonging to a different nation: it’s that combination of the intense, close up, far-flung and wide-ranging, which seem to be the essential qualities.

For a lot of us the Gate is a pool you can go back to when you have been made to feel rather desiccated by some of the work that’s been going on elsewhere.

There are times when you feel like you want to go back to something which is speaking with an obvious urgency, and often sublime assurance, and wonderful Rolls Royce efficiency. That’s of course not fair to a large proportion of theatre.

The internationalism is very core to what’s important. Scale doesn’t mean restriction.

When journalists – many of whom of course hate the theatre – talk about the ‘average theatre goer’ they very often complain about the age of theatre goers and how embarrassing it is to be in the theatre and how stuffy it is and so on. I would tell them to go to the Gate because actually first of all, there are plenty of older people, but you also see plenty of younger people, and you see people who have been willing to take a chance on what they see. In the way that you might in the old days have taken out an extra library book, and I think that’s really important.

This is partly a question of ticket prices as well. If the ticket price isn’t exorbitant, and if the approach to the theatre (physically) and the surroundings when you’re actually

‘She is one of the Gate’s great discoveries’

Susannah Clapp on Rosie Elnile

in it aren’t intimidating, and don’t make you feel like you’ve got to go and have a meal with a lot of napery afterwards, then you’ve won an important battle. That’s very important for the ecology of the theatre. Some of that is true of a lot of small theatres. But that combined with the internationalism, the feeling of attachment to the Gate, it is very good that should be combined with this wide international reach.

Talking about the Gate and the effect it’s had too – especially with designers – with Rosie Elnile…we’ve followed her with a lot of interest here and elsewhere. Perhaps people are lucky early in their careers to be taken on by the Gate.

For design though, it’s been quite extraordinary, like I said, in some cases, literally cracking open this small space, which pushes an audience away or brings them into the action, or in any way makes them very conscious of their relationship to the stage, I think has been exemplary.

And I can’t believe that hasn’t had an effect elsewhere.

From the cutting room floor…

#1

EM

Just going back to that as well, something I was so delighted and fascinated to read in one of your reviews.

It was to do with the window. You had written that he [Mick Gordon] as his final show had presented a piece of work that was a work in progress [that used the window.]

SC

I’d forgotten this. Now I look at it I remember it.

EM

It’s funny because when Rosie and I found the window we thought it felt like a feature of the Gate. We thought no one’s ever done this. And then you spend five minutes going through the archive and realise they have. I wonder if there’s a truth in that [The Gate] enables artists to feel like it is theirs.

SC

I suppose that’s to do with it being slightly provisional as a space perhaps: and again not too big – with nothing absolutely fixed there.

EM

And you would think in a space that is so bold in its way of conceiving what theatre can be we might. I mean funnily enough, Jude Christian’s plan for Trust (2018), which was her show in my first season, had an idea early on that all of the spaces in the theatre would be part of the show. It was about the financial crisis. She had the mezzanine, with the bedroom upstairs. And actually the foyer was sort of an installation, it was made like a building site, as though we were going to develop it into a luxury flats. And then in the loo there was a ‘Learn Chinese’ or ‘Learn Spanish’ advert for businesses.

#2

SC

Marathon was very interesting to me because it was an example of what the Gate can do and has done supremely well – which is to project a very strong visual image in the staging, in an intimate space. And it was a two hander. But it also showed some of the difficulties of that kind of work, it seemed to me, because the script fell so far short of the visual image.

EM

Oh that’s interesting.

SC

Perhaps you don’t want any disappointments in this conversation!

EM

No, it’s all part of it!

SC

What I retained from Marathon is the central image of two men running at different paces round the small stage with us gathered around them.

EM

Oh I see. Literal marathon running.

SC

Yes. It was a very expressive design and stage movement – and I’d forgotten, when I was thinking about talking to you about the Gate, that I thought how strong and innovative much of the design has been in the theatre. It wasn’t until afterwards when I looked up my review and found that I’d been pretty much bored by the script – of course, that’s an ugly memory, but something must have gone wrong in the conversation of what the design and the script should be doing. Sometimes I suppose there is an interesting lesson to be learned about the theatre – that we retain one element and the less, to me, satisfactory element of it died away.